As I was studying 2 Chronicles last week, the following passage stopped me, and I remembered a word study that I made a few years ago.

Now when the priests came out of the holy place (for all the priests who were present had sanctified themselves, without regard to their divisions), all the levitical singers, Asaph, Heman, and Jeduthun, their sons and kindred, arrayed in fine linen, with cymbals, harps, and lyres, stood east of the altar with one hundred and twenty priests who were trumpeters, it was the duty of the trumpeters and singers to make themselves heard in unison in praise and thanksgiving to the Lord, and when the song was raised, with trumpets and cymbals and other musical instruments, in praise to the Lord,

‘For he is good,

for his steadfast love endures for ever’,

the house, the house of the Lord, was filled with a cloud, so that the priests could not stand to minister because of the cloud; for the glory of the Lord filled the house of God (2 Chronicles 5:11-14).

That word "glory" has rich meanings, back to passages we've looked at and forward to the New Testament. The word can mean honor/renown, or beauty/magnificence, or heaven/eternity itself. St. Ignatius’s famous motto was Ad maiorum Dei gloriam, “to the greater glory of God.” I always took this to mean, “to increase God’s renown (through our devotion and service),” but the Jesuit theologian Karl Rahner notes that we also share in God’s own life as we serve God.[1]

When I was a little kid, we learned that catchy song "Do Lord", with its image of sharing God's life eternally.

I’ve got a home in Glory Land that outshines the sun

I’ve got a home in Glory Land that outshines the sun

I’ve got a home in Glory land that outshines the sun

Way beyond the blue.

I was little and misunderstood what “outshines” means. Instead of “shines brighter than the sun,” I thought it mean “sunny outside.” So I had an image of Heaven as being outdoors and pleasant, like summer days with no school.

Carey C. Newman, writing in The New Interpreter’s Dictionary of The Bible (pages 576-580) notes that the biblical words for “glory” are kavodh and doxa; that second word provides the root for “orthodox” and “doxology.” Newman states that the word applied to God can mean appearance or arrival, as at Sinai or the Tent of Meeting or the Temple. This is the special Presence of God (Shekinah), sometimes depicted in “throne” visions (as in the famous Ezekiel 1 and Daniel 7, and also the non-canonical 1 Enoch 14), and also the presence of God which dwells in the tabernacle (as in the Priestly history, e.g. Exodus 40:34-38).[2] Moses and Aaron are able to mediate between the people and God, because at this point in the biblical history, God’s glory is dangerous, as in Lev. 9, when the sons of Aaron are killed, and also the later story in 2 Samuel 6, when well-meaning Uzzah touched the ark when it was being carried improperly on a wagon. The presence of God is also associated with the cherubim and the mercy seat (Ex. 25:22, Num. 12:89, Deut. 33:26, 1 Sam. 4:4, Ps. 18:10, Ezek. 9:3, 10:4, Heb. 9:5).

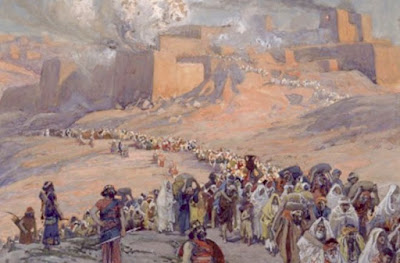

God’s glory dwelled in Solomon's Temple (2 Chr. 5:13-14), and frighteningly departed from it prior to the Babylonian conquest (Ezekiel 8-11). Biblical scholar Jacob Milgrom likens Solomon’s Temple to Dorian Gray’s picture: the people’s sins “collected” there, necessitating periodic sin offerings in order to remove the uncleanness. Gammie notes, though, that the people’s sins became so dire, numerous and ongoing, that these offerings no longer sufficed, even those of the Day of Atonement. Thus, the result of which was the loss of God’s Shekinah and inevitable foreign conquest of Judah and Jerusalem.[2]

Glory is not the same thing as holiness, but God’s glory and God’s holiness are closely connected as attributes of God and aspects of God’s manifestation---as well as the discipleship we pursue “for the glory of God.” It is difficult to find a modern analogy to the biblical idea of holiness: something powerful and necessary to handle properly (like fire or electricity) but also something “contagious,” from which one must be cleansed through prescribed means. One had to perform purity rites when one touched something unclean/unholy, like blood or a dead body. One had to perform sacrifices and priestly activities in a prescribed way, not to endure nit-picky rules but in order to handle something very powerful in a safe way.

The holiness of God is reflected in Israel’s life in the Torah’s distinctions between unclean and clean, holy and common, and sacred and profane. We may wonder about the ideas of cleanness and uncleanness because of texts like Acts 10:9-16, but in Israel, these were God-given parameters for how to live and how to relate properly to God, not only according to God’s expressed will but according to God’s revealed nature, the Holy God who dwells in Israel. (cf. Zech. 2:13-8:23; 14:20-21). As we read in Ezra and Nehemiah, these God-given parameters were crucially important for the people's faithfulness and well-being.

God stipulates holiness on the part of his people because he desires to create Israel as his own people and to be in covenant with them. To be associated with God is a call to be pure and clean as well. I become impatient when people isolate the Ten Commandments from other biblical material (as, for instance, important statements in the history of law, or as general moral guidelines). The commandments function as those things, but you must notice that they are first given in context with God’s covenant with the people of Israel. God first gathers the people at Sinai and makes a covenant with them (Ex. 19), and only then gives them laws. Within those laws, in turn, God provides means for repentance and atonement for sin. In other words, God’s grace and love always precedes and encompasses the ethical aspects of God’s will, not vice versa; you could say his glory is revealed in love.[3]

Holiness not only has distinctions of clean and unclean, but also justice and righteousness—again, reflecting the glory of God as the just and righteous Lord. Holiness is never understood (properly at least) as only a concern for right ritual, cleanness, and restoration from uncleanness. Israel also witnesses to God through acts of justice, provision, and care for the needy (Lev. 19; Ps. 68:5). As the Baker Dictionary puts it, “it is the indication of the moral cleanness from which is to issue a lifestyle pleasing to Yahweh and that has at its base an other-orientation (Exod. 19:6; Isa. 6:5-8). Every possible abuse of power finds its condemnation in what is holy. Those who live in fear because of weakness or uselessness are to experience thorough protection and provision based on the standards of righteousness that issue from God’s holy reign (Exod. 20:12-17; Lev. 19; Ps. 68.:5).”[4]

Among other aspects of God’s glory, there is also a “royal theology” of glory, e.g. the books of Chronicles and also Psalm 24, where God’s glory, the human king, and the establishment of the Jerusalem sanctuary are all connected. As Newman states, “The regular enjoyment of Yahweh’s divine presence, his Glory, forms a central part of Temple liturgy and democraticizes the unqualified blessing of God upon king, Temple, nation, and world. Glory in a royal context assures of Yahweh’s righteous and benevolent control over all.”[5]

Newman continues: the biblical concept of Glory also has to do with judgment, as in Jer. 2:11-13, Hosea 10:5-6, and others. God demands holiness from his people and eventually God must deal with sin. But God’s glory also connects to forgiveness, restoration, and hope---notably in the poetry of Second Isaiah: “The arrival of Yahweh [in the transformed Jerusalem] not only restores what once was—the glories of a Davidic kingdom—but also amplified. Mixing Sinai with royal imagery, the prophet [Second Isaiah] speaks of a day when the Lord will once again “tabernacle” in Zion. This time, however, Yahweh will “create” a new (and permanent) place for his Glory to rest.[6] (p. 577).

According to Newman, there are several important aspects of the New Testament theology of glory.[7] All these references are worth looking up and thinking about.

* The continued use of glory to mean God’s appearance and presence (Acts 7:55, Heb. 9:5, etc.)

* The Son of Man theme is connected to glory and the throne of glory (Mark 8:38/Matt. 16:27; 19:28; Luke 9:26; Mark 13:26/Matt. 24:30; 25:31; Acts 7:55, 2 Peters 1:17).

* The many depictions of glory as an eschatological blessing: Jude 24, Heb. 2:10, Rev. 15;8, Rev. 21:11, et al.) As Paul says, the glories of redemption make present day suffering pale in comparison (Rom. 5:2, Rom. 8:18, also 1 Pet. 4:13 and 5:1). At that time we will share in glory (2 Thess. 1:9-10, etc.).

* But this future glory is not just a long-from-now time, but also something we share in Christ now, as in Col. 1:17, 3:4, Titus 2:13)

* Also glory as resurrection, as in Rom. 6;4, 1 Cor. 15;25, Phil. 2:5-11, 1 Tim. 3:16, 1 Peter 1:21, Rev. 5:12-13, et al. Hebrew 2:9 applies Ps. 8 to Jesus even though it is not a “messianic” psalm.

* And glory and Christology, as in the beautiful Heb. 1:1-14.

* Paul also calls Jesus the Lord of Glory (Eph. 1:17) and connects Jesus to the glory of god in 2 Cor. 4:6, and 2 Cor. 3:18.

We can see two aspects of the powerful quality of holiness in Jesus’ life and death. Notice that when certain people (and demons) in the Gospels encounter Jesus, they want him to go away (Matt. 8:34, Mark 1:23-25, Luke 8:37, even Luke 7:6). That’s not because he was unpleasant; it was because they perceived that he was holy—and holiness is dangerous for mortals to encounter, as we've seen in some of the Old Testament stories. People thought that Jesus had to be approached in a way befitting God’s powerful holiness.

As God’s glory “dwelled” in the tabernacle and temple, now that glory dwells in Jesus: John 1:14 doesn’t just mean that Jesus lived among the people of his time, but that the glory of God itself was visible and present in Jesus (also Heb. 1:1-4). If blood has a power (related to cleanness, uncleanness, and holiness) powerful enough to cover people’s sins in the days of the tabernacle and temple, the shed blood of Jesus (in traditional theology about the Atonement) is powerful enough to cover people’s sins, 2000 years later and beyond.

Ideas of holiness that reflects God’s glory are strong New Testament themes, too. The purity and justice to which Christians are called are Spirit-given gifts and, as such, are God’s own holiness born within us which empower our witness to others (e.g., 2 Cor. 5:21, 2 Pet. 1:4). As one writer puts it, “[God’s] character unalterably demands a likeness in those who bear his Name. He consistently requires and supplies the means by which to produce a holy people (1 Peter 1:15-16).”[8]

God’s glory and holiness extends to the sanctification of believers, who are called hagioi, “saints” or “holy ones,” over 60 times in the NT. As one writer puts it, the outward aspects of holiness in the OT are “radically internalized in the New Testament believer.” “They [the believer/saints] are to be separated unto God as living sacrifices (Rom. 12:1) evidencing purity (1 Cor. 6:9-20; 2 Cor. 7:1), righteousness (Eph. 4:24, and love (1 Thess. 4:7; 1 John 2:5-6, 20; 4:13-21). What was foretold and experienced by only a few in the Old Testament becomes the very nature of what it means to be a Christian through the plan of the Father, the work of Christ, and the indwelling presence of the Holy Spirit.”[9]

Thus, New Testament ideas of glory stress Jesus’ dwelling among us, and the gift of the Holy Spirit in believers. If you appreciate the Old Testament passages about the in-dwelling of God’s glory, you may be taken aback by the idea that the Lord God Almighty, whose glory was so dangerous to approach, is present in us NOW through the Holy Spirit.

In fact, as a spiritual exercise, read biblical passages that reflect a very “majestic” view of God’s glory (e.g., Exodus 40:34-38 and Deut. 5:22-27), in conjunction with passages like Romans 3:21-26, Heb. 1:1-4, and Heb. 4:14-16. Don’t think that the more “scary” passages about God’s glory have been superseded by the New Testament; think instead about how the same God who dwelt among the Israelites now dwells with you in the Holy Spirit—exactly the same God upon whom you call when you’re desperate and in trouble, who will help you!

(This post is adapted from an earlier post on another blog: http://changingbibles.blogspot.com/2012/04/ill-be-moving-these-posts-to-journey.html)

Notes:

1. Karl Rahner, “Being Open to God as Ever Greater,” Theological Investigations, Vol. VII, Further Theology of the Spiritual Life 1 (New York: Seabury Press, 1977), pp. 25-46.

2. Carey C. Newman, “Glory,” The New Interpreter’s Dictionary of The Bible, D-H, Vol. 2 (Nashville: Abingdon Press, 2007), pp. 576-580.

3. For all this discussion, see John G. Gammie, Holiness in Israel (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 1989), 38-41.

4. “Holiness,” in Walter A. Elwell (ed.), Baker Theological Dictionary of the Bible (Grand Rapids: Baker Books, 1996), page 451.

5. Newman, 577.

6. Newman, 577.

7. Newman, 578-580.

8. “Holiness,” 340-344.

9. “Holiness,” 343.

I also found this interesting article via Twitter: http://www.huffingtonpost.com/roger-isaacs/how-did-the-biblical-glor_b_905944.html